Mobility as a Service (MaaS)

Laura Del Vecchio

skyNext @ adobe.stock.com

Key Considerations

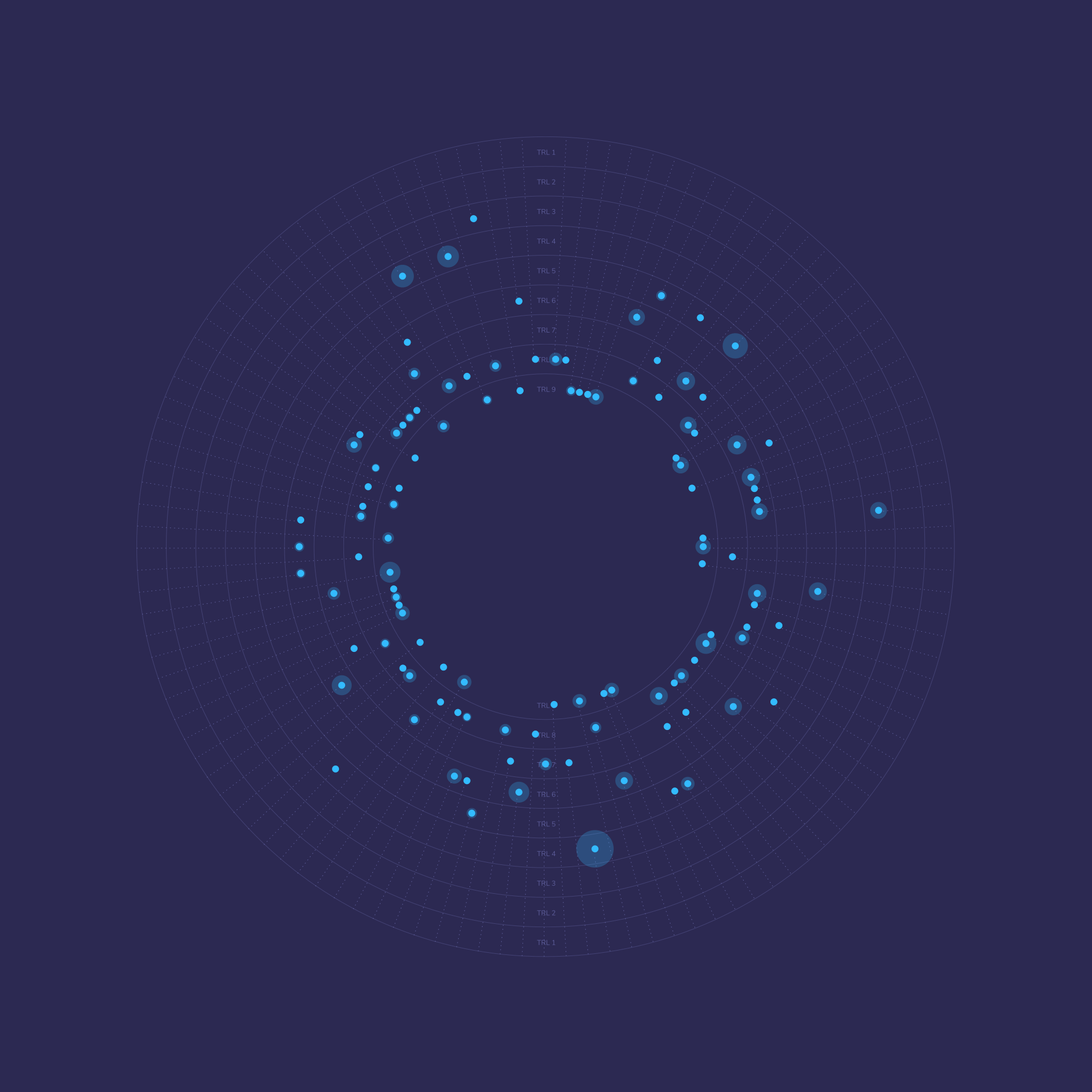

Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) is a business model that encompasses the use of emerging technologies to improve all aspects of transportation through servicification. Servicification is a way of transforming existing systems or processes into discrete services, with the aim to aid and ease procedures. Facilitated by advanced mobile information and communications technologies, such as Mobile Crowdsensing Platforms, it complements a broad range of innovations in the mobility sector —from Self-driving Cars to Real-time Mapping.

Although MaaS is a broad concept, from a functional viewpoint, it relies on real-time information gathered from sensors attached to public transportation, Geospatial Data Generation Tools, Multimodal Transportation Ticketing, and Single e-Payment Platforms. Overall, MaaS takes shape through integrating different tools and platforms that allow seamless transactions between end-users and providers of transportation services.

With a growing interest in sharing services instead of ownership, MaaS is proving to become a reliable option for commuters that do not desire to purchase a personal vehicle but still need safe transportation. By looking back in history, MaaS services started appearing during the mid-2000's financial crisis as a way for individuals to make a profit from excess capacity. With the emergence of the Sharing Economy, business models are shifting, which has manifested itself in numerous applications in the field of transportation. For example, people owning private vehicles were making profit from vehicle-sharing rides while offering lower ticketing rates to passengers. Also, other sharing initiatives include the renting of e-scooters or bicycles.

A Solution or a Patch to Avoid Real Change?

From a rhetoric perspective, most dominant opinions about MaaS benefits highlight only its positive effects.

Companies within the Sharing Economy branch depend on MaaS development, such as Waze, Car2Go, CoWheels, BlaBlaCar, and many more. However, these companies have produced unintended consequences to existing transportation models, such as deteriorating labor conditions for traditional taxi services (e.g., Uber) or congested dock-based bike-sharing (or more recently, e-scooter) systems where private companies (e.g., Obike) compete for space in public areas. In Spain, after a successful and operating year, Obike disappeared from the streets and left their users without their deposit (to sign up, users were requested 49€ deposit). In these cases, we can see that instead of creating a mobility package model that aggregates all transportation assets, the outcome is generating a competition scheme that does all but integration.

In megalopolises like São Paulo, companies such as Uber are frequently claimed as a substitute for public transportation in some jurisdictions where transportation is precarious or nearly nonexistent. It was noted that, in some of São Paulo's neighborhoods lacking access to decent transportation options, investments in public mobility decreased because many users preferred taking Uber trips instead of a bus route. One of the most significant risks of this scenario is the dependency on private services that can jeopardize mobility resilience rather than extending it. For instance, if these companies fail or break, neighborhoods accustomed to rely on these businesses may see themselves car-less, and consequently, without access to mobility because public-necessary services were in short supply when they should have been invested in.

Another considerable hurdle for MaaS is a reliance on digitalization. As many of the sharing economy companies depend on online platforms for operating rentals and sharing deals, communities without access to personal smartphones, for example, could experience exclusion from this service. Additionally, unbanked individuals relying on cash at the point of use could be paying more for these services as traditional payment methods would no longer operate (e.g., depending on intermediaries, illegal transactions, etc.).

The plan of integrating all transportation modes has been one of the biggest purposes of transport authorities; this is the reason why MaaS sounds so appealing. However, deploying MaaS properly is intricate and demands huge commitment from public authorities, decision-makers, and stakeholders. The classic chicken vs. egg paradox presents itself in the difficulty of gaining critical mass, including service providers and end-users. A solution would be to create a single MaaS platform for continuous collaboration on both sides. This would require the right proportion of users to guarantee an acceptable level of added-value and sustainable growth. Further barriers to entry lie in the attempt to collaborate between multiple stakeholders in both private and public sectors —often with conflicting business models. A complete restructuring of the supply chain of mobility service providers may be necessary and would require integrating transportation data, data infrastructure, and physical transport infrastructure, which by itself, is a considerable challenge.

Future Implications

By combining and repackaging different modes of transportation, including public transit, MaaS offers a tailored mobility package that aims to be user-centric, flexible, personalized and on-demand. A subscription-based approach could facilitate personalization and allow framing mobility services around traveler preferences. If combined with conventional public transport services, the transportation network would be strengthened even more. For businesses, MaaS initiatives aim to unify all modes of transportation into one simple and easy-to-use platform to reduce cost and improve efficiency by decreasing travel planning and administrative overhead.

Transportation suppliers could charge a monthly or fixed percentage of sales instead of building the infrastructure. Solutions could be personalized for access to specific routes; modular pricing with real-time payments according to road conditions, days of the week, holidays, and time of day, etc., would also be possible. Users, on the other end, will be able to hyper-configure their profiles, choose from a variety of modes of transportation, gain access to each one, and make one monthly payment according to their usage.

Finally, MaaS could help decarbonize the transport sector by reducing the use of single-user cars and encouraging the diffusion of electric vehicles. Although moving from private car usage to alternative modes of transportation is a significant paradigm shift and could, in theory, prevent the negative effect of current transportation systems on the environment, in practice, carbon emissions have occasionally increased as car-less individuals decide to switch from public transit to car-sharing vehicles. This proves that MaaS is no solution to all transportation dilemmas. Robust state authorities and policymakers will be required to put in place a strategy that can help create a more reliable mobility system while also avoiding car-dependency.