Sustainability Labels

Laura Del Vecchio

endostock @ stock.adobe.com

Behind a package, there is a product containing manifold processes invisible to the consumer. The use of labeling is a common practice in recent years, especially for nutritional facts and ingredient lists in reference to food. Yet, consumers are demanding additional information from companies, questioning if the products they buy comply with basic requirements following ethical and environmental practices, such as the carbon footprint of a specific product.

Key Considerations

Labeling products to inform customers of what is inside is nothing new. However, for over three decades, many public and private enterprises have been one step ahead in the process of categorizing and labeling. Globally, many brands started to add additional logos to their products that certify their manufacturing practices, as well as the handling of the goods, or even if their product is free from child-labor exploitation. Current examples of prominent initiatives range from Fair Trade and Rainforest Alliance labels and many other carbon indexing schemes as well as vegan and animal welfare logos. A survey conducted by the European Commission in 2012, identified 129 both public and private sustainability food data schemes available in the EU. Also, according to Ecolabel Index's recent research, there are approximately 456 ecolabels in 199 countries and 25 industry sectors.

This rise in labeling is mainly down to consumer demands as people become exponentially concerned about the impact their consumption produces on the planet. The carbon lifecycle of food, for example, includes the use of fertilizers, the emission of gases from manure, livestock digestion, as well as packaging, food processing, and transportation. All aspects that consumers are starting to be interested in when consuming. The restaurant chain Just Salad, for instance, started displaying the carbon footprint of every item on their online menu. They became the first restaurant in the U.S. to estimate the greenhouse gas emissions associated with the production of each ingredient on the menu item, a type of data based on research and calculation of carbon emissions associated with hundreds of produce.

Nevertheless, the term "sustainability" is broad and multidimensional. On the one hand, there are environmental issues within these labels that do not necessarily respond to trade-offs between consumers and companies (e.g., trust, reliability, accountability, etc.). On the other, the social dimensions are more related to ethical issues, such as child labor. The results of using sustainability labels are hard to measure, especially taking into account that the implementation of such methodology is considerably recent. The long-term outcomes associated with sustainability labels are yet to be analyzed, but some emerging technologies are starting to document and track possible dimensions related to this practice. These solutions shed light on consumption patterns and enlighten if such standard motivates behavior change —or not.

Technological Solutions Involved

Together with blockchain solutions, certification processes could be easily automated, better synchronized, more transparent, and more difficult to tamper with. The technology application Blockchain Certificate is currently being used in the supply chain to increase traceability, helping plunge gray markets and triggering the emergence of novel innovations, such as the creation of technological objects. For example, as the blockchain market is exponentially growing, especially in the food sector, many companies are considering creating a shared data platform, similar to Bartering Platform, to compare their products and increase market competition, as well as adding value to their products.

Other solutions include tagging products with the help of methods such as Nanotagging. This labeling variety is being introduced by manufacturers and supply chain companies to make labels harder to be removed and to integrate smart designs into their stocks. Solutions include Invisible Traceable Marker, a type of ink added to packages that can sense the counterfeit product's lifecycle integrated into QR codes that verify their authenticity. Current examples are used in the fine wine and spirits industry, but it is expected to reach other sectors in the near future.

Key Players

Starbucks: Coffee farms have a considerable impact on the environment and also in labor terms. The Rainforest Alliance standard requires coffee farmers to replant trees on their coffee crops and to ensure fair working conditions to their workers. Starbucks has recently entered into this standard by dedicating its efforts to helping farmers overcome poor labor conditions often faced by coffee communities. In a recent report, Starbucks committed 100 percent of their coffee to be ethically sourced, thus improving the quality of their products as well collaborating to sustainability.

Carbon Calories: Beyond carbon labels, there are research initiatives that store and analyze data related to the carbon footprint of products. Carbon Calories have started reporting to consumers the carbon footprint produced by their consumption patterns. The platform compares products and uses an arithmetic metric against a daily carbon quota displaying the environmental impact consumers have on carbon emissions.

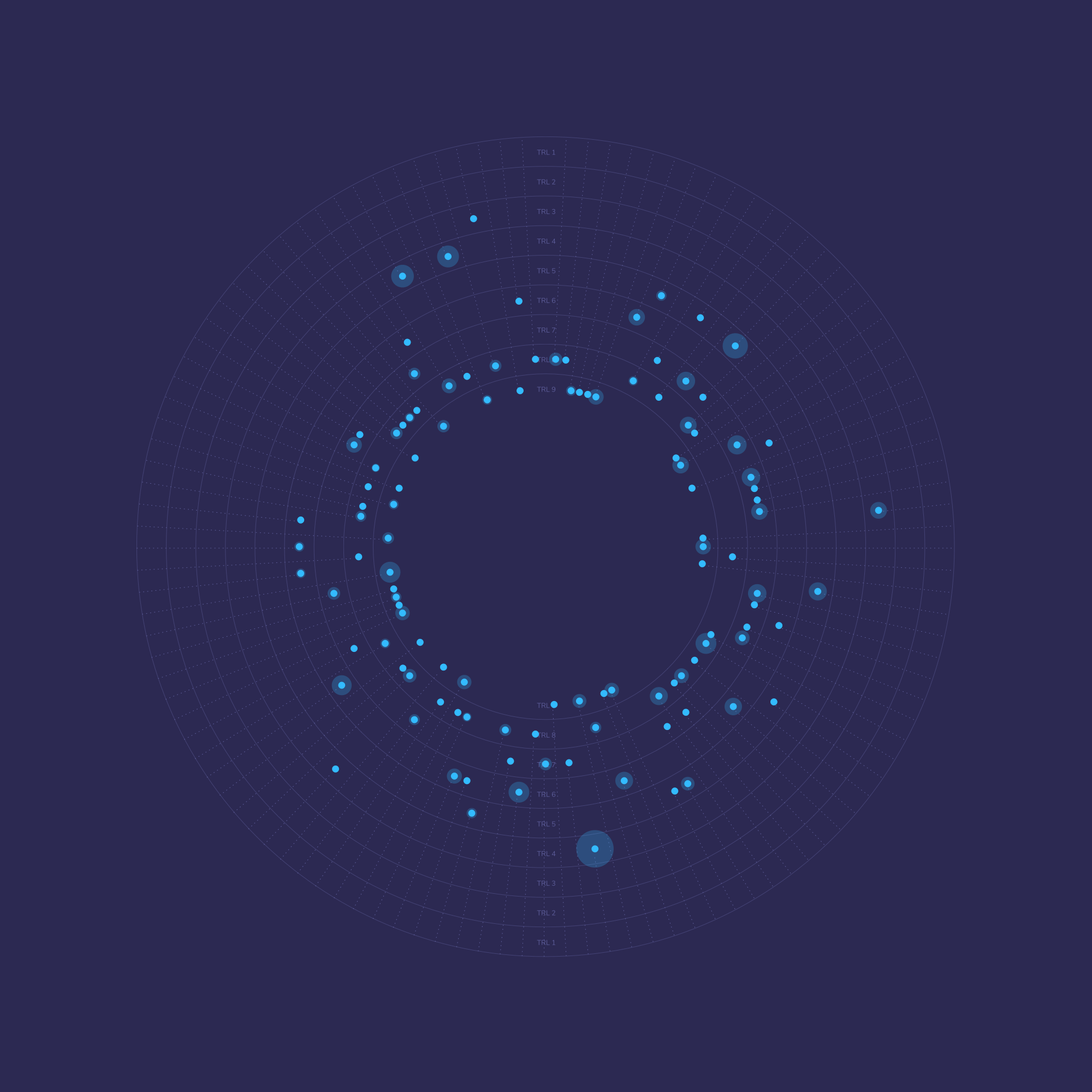

Sourcemap: The MIT Media Lab born project Sourcemap is a collaborative Mobile Crowdsensing Platform that stores data about the environmental footprint of products worldwide. The database shows information regarding various stages of manufacturing, but also on packaging and transportation. The data, displayed in map form, includes the composition of the product, the origin of raw materials, the destination country, and all other aspects that include information about a product's social and environmental impact.

Opportunities & Challenges

When labeled, a product complies with several criteria that is verified by trained professionals who pay periodic visits to industrial or supply chain facilities to validate their processes according to a standard methodology. For instance, a farmer who complies with regenerative practices, such as not applying toxic fertilizers and not using child-labor, could have access to a specific certification. In turn, they could sell their produce for a fairer price to companies who want to comply with these criteria.

Current regulatory efforts are working on expanding the limits of ethical product labeling. Nowadays, this system is commonly found and mostly limited to alimentary products, but this could become a good opportunity for governments and companies to be certified regarding their social accountability. Beyond labeling products, the certification process could propose myriad quality control tags to each part of the supply chain or administration procedures.

In general, sustainability is an aspect that awakes the interest of many, but in terms of food choice, consumers' consumption habits compete with other issues such as quality, healthfulness, and taste. This means that sustainability may not necessarily correlate to the main factor consumers consider when choosing a product. As a real challenge, some experts warn that it is not only the specifications of a product that drives them to consume but the motivation behind the brand and the product itself. Horne (2009, p. 175) affirms that “(…) consumers remain full of intent to purchase sustainably, yet these stated preferences have not translated into a widespread uptake in the purchase of more sustainable products.” Other attributes such as price, the brand, and the nutritional information bid directly with sustainability labels in terms of consumer knowledge and choice preferences. It also varies on whether consumers truly know what these labels mean and their capacity to make use of the data. If the labels are not broadly known or if their labeling is not completely clear, even a knowledgeable consumer won't take the risk of consuming them.