A Supply Chain Act to Prevent the Sky from Becoming a Sheet of Smoke

Laura Del Vecchio

Matt Palmer @ Unsplash

From 2019 until late 2020, global society witnessed many fires taking place, from north to south, east to west. In the United States, almost a hundred wildfires destroyed entire towns and burned more than 4.6 million acres on the West Coast, forming a sheet of smoke visible on the International Space Station. During Australia's annual bushfire season in 2020, fires intensified and spread across the country due to increased and unusual temperatures related to Climate Change. In Indonesia, last year's fires led to a 0.84 percent loss of its total landmass, largely due to plantations that produce palm oil.

Brazilian Indigenous Peoples

Celio Messias ©Clio @ stock.adobe.com

Brazilian Indigenous Peoples

Celio Messias ©Clio @ stock.adobe.com

Further, from August to September 2020, the Amazon rainforest experienced a more severe dry season, attributed to warmer temperatures in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean according to scientists, which was also responsible for unleashing the perfect conditions for human-set fires to spread. The fires, which generally occurred in deforested areas and farmland, extended to protected virgin forest zones. On the same note, fires in the Pantanal forest, the world's most extensive tropical wetlands, located across Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia, are associated with rainforest fires too. According to Brazil's national space agency INPE, there were three times as many forest fires in 2020 than in 2019, responsible for threatening the lives of local fauna and flora, as well as Indigenous Peoples, who fight daily to protect the lands from deforestation and highly depend on the forests for their survival.

Tofu Is Not the Problem: Your Beef Is

A year since images pictured the world's lungs becoming an inferno, the Brazilian forests have not yet stopped burning. For the scientific community, the association between increased fires across Brazilian territory and soy production is nothing new. In fact, ever since the Brazilian currency devaluated considerably, the country became more competitive internationally by offering lower soybean prices in the market. This subsequently led to a boom in soy cultivation and cattle-ranching, increasing the production of soybeans for livestock feed. The expansion of soy farmlands, which were initially reserved to already deforested land previously under pasture, allowed cattle-ranching to spread to other areas, culminating in further deforestation.

The global appetite for beef —against all odds that some claim to be tofu's fault— is raising the demand for agricultural commodities, consequently enhancing the value of land to be transformed into farmland. In a report released by Chain Reaction Research (CRR) in May 2020, a surge in cattle farming in the past two decades, led by the big food companies, is possibly related to the increased deforestation in the Amazon. According to CRR's findings, the link between an extended number of new fires occurring near the areas owned by these companies is not a coincidence.

The Amazon seen from above, captured by NASA's satellites

NASA @ NASA Earth Observatory

The Amazon seen from above, captured by NASA's satellites

NASA @ NASA Earth Observatory

Indeed, according to NASA's satellite monitoring system, between July and October 2019, 417,000 fire alerts were detected inside some companies' potential buy zones, representing almost fifteen percent of the total fire alerts in the regions near meatpacking plants. Yet, though this does not accuse these companies of starting fires, according to Marco Túlio Garcia, a researcher at Aidenvironment, the CRR research's "[...] goal was to show the occurrence of an enormous quantity of fires in the proximity of these companies, which does not implicate the direct involvement of the companies with these practices. But some questions do need to be answered with respect to their supply chains."

Almost two decades since the implementation of the Amazon Soy Moratorium (ASM), an agreement set between grain traders not to purchase soy grown in deforested areas, deforestation rates between 2004 and 2012 decreased considerably. However, many experts argue that the initiative is still profoundly reliant on deforestation monitoring and compliance regulations —which, currently, are lagging behind.

Global Deals Shattering

According to an investigation conducted by The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, while for the first decade of the moratorium soy-driven deforestation decreased, nowadays companies are still allowed to keep trading with farmers who "[...] have been caught illegally felling rainforest, so long as the soy originates on other farmland, free of illegal deforestation." The investigation sheds light on potential gaps in the moratorium monitoring system, where corruption and fraud allow doors to open for indiscriminate soy laundering and triangulation, a system where landowners venture to sell "dirty soy" through "clean farms." Accordingly, a report published by Repórter Brasil suggests that some property names, in the state of Mato Grosso, Brazil, were changed in order to omit the origin of soy and the links to farmlands accused of environmental damage.

Amazon Rainforest burning

Tobias Seidl @ Unsplash

Amazon Rainforest burning

Tobias Seidl @ Unsplash

Despite Brazil's claim to be the world's most sustainable agriculture, the constant menace of fires, the lack of supply chain monitoring, and ineffective law enforcement indicate otherwise. As suggested by recent research, even though most of Brazil's agricultural products are considered deforestation-free, 2% of properties located in the Amazon and Cerrado (Brazil's biggest biomes) account for 62% of all illegally deforested areas and 20% of soy exports are tarnished by illicit deforestation. Along with these staggering numbers, vast quantities of beef and soy exported to Europe from Brazil are contaminated by deforestation, with about a fifth of soy and roughly 17% of beef destined for the European Union from Brazil's Amazon and Cerrado biomes likely to have come from deforested farmlands.

Initiatives such as the Mercosur-EU trade deal, a recent agreement made between the EU and the Mercosur group of Latin American countries (Brazil included) that requires EU imports to follow the export countries' legislations, could well prevent European supply chains trading with deforestation meatpackers. However, the increased spread of fires in Brazil may block the trade deal, as threatened by Emmanuel Macron.

'Act Now!'

Act Now! Campaign

Markus Spiske @ Unsplash

Act Now! Campaign

Markus Spiske @ Unsplash

Establishing a complex tracking system capable of tracing the origins of products or enforcing clear policies on deforestation could deem positive results. Still, the rising global demand for food —and especially meat— puts increasing pressure on the soy and cattle supply chain and leads to incentives preventing the agri-food system from acting effectively against increased deforestation rates. One reason for this is meat-based local dishes are deeply rooted in Brazilian as well as European cultural heritage.

Raising awareness among the global population about the consequences of a plate that seems innocent at first sight is therefore as important as promoting policies, tracking systems, and international cooperation to preserve the forest, its soil, and thereby, the atmosphere. Urgent and collective discussions are needed to come up with new solutions encompassing ecological safeguarding measures, as well as strategies that respond to the global demand for food.

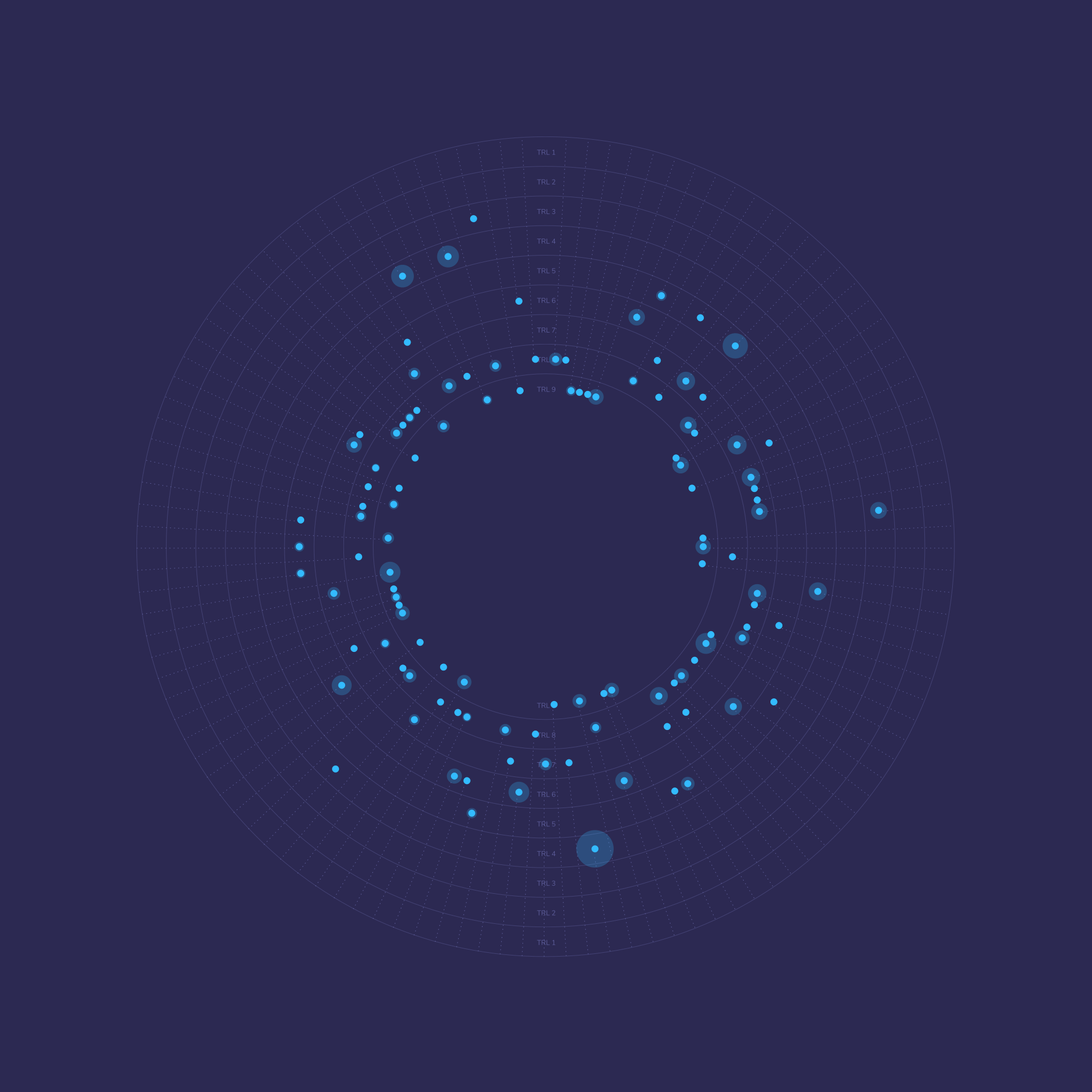

In an effort to encourage analyses and debates on sustainability, Envisioning, together with the GIZ projects i4Ag, Promoting Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains, and the GIZ techDetector team, designed a workshop called techJourney. This workshop invites participants to analyze the potential repercussions of applying emerging technologies to specific contexts, and always with an eye on sustainable practices.

Let Our Experts Have Their Say

The workshop took participants into a world-building exercise set in 2026, a year marked by raging human-set fires in the Amazon rainforest, responsible for clearing 65% of the local landmass, thus endangering local fauna and flora as well as Indigenous Peoples, to give way to cattle and soybean fields.

💡

Does this sound familiar to you? Future scenarios do not need to be set far into the future. Changes occurring now can uncover positive or negative outcomes tomorrow; it all depends on how we act upon our present actions.

With that in mind, participants were grouped into three task forces responsible for imagining responses that could tackle the soy and cattle-related fires with the help of emerging technologies. The task forces ranged from the Human Rights Advocacy Network of NGOs, GIZ Working Unit in Agricultural Value Chains, Traceability, and Innovation, and a Company Selling Feed for Livestock in Europe.

To explore participants' proposals and ideas, the following paragraphs are dedicated to sharing their conclusions.

The Human Rights Advocacy Network of NGOs

This task force aims to create a project capable of tracking deforested zones and ensuring soybean and cattle farms do not occupy protected areas. There is also a need to make sure Indigenous Peoples are not negatively affected, and their demands are equally heard.

Indigenous Peoples' lands

Sébastien Goldberg @ Unsplash

Indigenous Peoples' lands

Sébastien Goldberg @ Unsplash

After discussing what could be done, participants decided to create a project that compiles a collection of comprehensive and emerging technological tools, designed to monitor deforestation maps and land-use activity. The project starts by harnessing satellite images and comparing them with geospatial data generated by machine learning tools. Then, the information is crossed with algorithms powered with legislative tracking systems, as an additional effort to differentiate legal from illegal deforestation linked to soy and beef production.

Additionally, the project includes a deep learning filter preventing fake, digital content from circulating between meatpackers and regulatory bodies, helping to spot fraud in the legal digital ecosystem. They also partnered with a crowdsourced app to give communities a voice against corruption, when local law enforcements fails to comply with environmentally sustainable achievements.

What Does the Future Hold for this Project?

This complex web of tools could track each soy grain from its origin, elevating compliance mechanisms to a new level of transparency. However, behavior change is also necessary. Many meatpackers may see ForestIntelligence as a threat to their businesses and therefore not have an interest in implementing this initiative. In this case, law enforcement may make all the difference.

Instead of placing this initiative as optative, local and international agri-food actors must adapt to local and international regulations in order to do business with soy and cattle. Policies would have to include a mandatory online environmental registry for each farmland and, for example, certified cattle transport permits for entire livestock.

This combination of advocacy, technology, and law enforcement may sound provocative now, but if introduced gradually, it could soften possible disputes between producers, sellers, consumers, and environmentalists. This proposal does not intend to be a techno-solutionist measure. Instead, ForestIntelligence aims to combine human efforts with the hallmarks of emerging technologies, putting life at the center of any operation.

GIZ Working Unit in Agricultural Value Chains, Traceability, and Innovation

The second task force was responsible for creating a sustainability label to certify that schnitzels —a traditional Austrian dish, where meat is pounded out thin, then breaded, and fried— made in Germany are free from deforestation. The task force must ensure that the exported meat is labeled correctly, which will demand tracking mechanisms to check a produce's provenance from its origins to the consumers' plate.

Smoke in the Amazon

Fernanda Fierro @ Unsplash

Smoke in the Amazon

Fernanda Fierro @ Unsplash

Their project uses a regenerative model that, together with tracking and automated audit systems, aims to put forward a smoke-free strategy that not only analyzes all publicly available information from companies exporting and importing soy, but clears the sky of carbon emissions too. The tracking and monitoring system starts at the origin; meatpackers must tag their products with an RFID tag containing data from the source, including labor conditions of the soy farmland workers, and carbon emissions released during the production and transportation. Then, by crossing the data collected from the tags, a machine learning compliance algorithm analyzes all available information, generating automatic audits on the companies involved in the soy trade.

The project does not stop there. Each company would have to install a fair number of CO2 absorbing streetlights on soy and cattle farmlands, as well as in cities and towns, to receive the labeling certification, a measure expected to improve the air quality of those living in the area, particularly Indigenous Peoples. Also, the sustainability label would demand that all beef producers support alternatives to soy in feed for livestock, such as plant-based meals made out of algae.

What Does the Future Hold for this Project?

One cannot judge a book by its cover. But, if the cover reveals information saying the author is involved in domestic abuse —even if the book is about equal rights for women and men—, perhaps readers would consider this when deciding whether to read it or not. The same goes for other products we buy.

Processes and practices behind a product, once invisible to the consumer, could be verified through sustainability labels, ensuring that what a brand claims to be true is also confirmed by trained professionals responsible for validating the information displayed on the packaging. This could surely increase transparency to existing supply chains, but would also help pressure corporate interests to become more sustainable, as investors, governments, and companies could decide who they want to do business with. For example, since the raging fires in Brazil received global attention, many investors flagged their concerns over the destruction of the rainforest, and claimed that if deforestation does not stop escalating, it will affect the conditions for investing in Brazilian businesses.

On the other hand, if companies decide not to invest in these businesses, smallholder farmers involved in soybean and meat production would see their household income directly affected. Solutions to this matter range from introducing a Universal Basic Income, capable of providing the necessary means to maintain the basic needs of these individuals, to training and educational resources to help give smallholder farmers additional employment options.

This project also contemplates critical points that may potentially pay back in the longer term. Considering that Indigenous Peoples' mortality rates are almost 150% higher than the Brazilian average throughout the pandemic, a project that takes care of the respiratory system of the local communities safeguarding the rainforest has an additional benefit. Protecting the lives of local communities that for centuries have preserved the forest should be one of the main goals of businesses involved with soy and meat production.

Company Selling Feed for Livestock

The last task force embodies a company selling animal feed to meat producers. The company, in this scenario, has made the difficult decision to not sell products at lower prices in illegal markets nor products without sustainability records. This task force aims to create a solution to prove to their international partners that their practices comply with human rights and environmental rules, throughout their production chain.

Livestock landfarm

Motoki Tonn @ Unsplash

Livestock landfarm

Motoki Tonn @ Unsplash

The proposal intends to set standards for geographic jurisdictions (a geographic determined zone under the legal authority of a court) with the help of computing schemes, such as Satellite Image Processing (SIP), in an effort to source soy only from already deforested areas, thus preserving Brazilian biomes. The project also includes AI-based systems that anticipate what consumers are likely to consume, an action intended to avoid excesses in the production chain. Finally, together with the blockchain land registry, they expect to encode the ownership status of Indigenous land. This solution automates certification processes and makes them more transparent to the actors involved in transactions with livestock feed, as well as making it more difficult to tamper with them.

What Does the Future Hold for this Project?

All in all, this project increases traceability and helps decrease gray markets involved in the soy and meat trade. As the blockchain market is exponentially growing, particularly in the agri-food sector, this could help create a shared data platform where producers, consumers, investors, governments, and all actors involved could compare products added to the ledger, as well as increase competition through sustainability, and therefore, add even more value to the products.

By combining computing solutions that both anticipate and monitor what happens on land, this project generates data that would be the basis for climate adaptation and mitigation policies. This would help decrease the jeopardies of Climate Change, support Indigenous Peoples' survival, and employ interactions between agriculture and forestry to overcome the perils of food insecurity and threats to local biodiversity.

The use of emerging technologies to create a web of detailed information of local land use and spatial data could become a toolbox for policymakers and stakeholders to help make more informed decisions. In fact, this project could be instrumental in setting fair international agreements between companies, investors, and governments in the agri-food sector, helping create policies to support food security worldwide and win the battle against shady trade agreements.

What Lies Ahead

The projects mentioned above are not intended to present techno-solutionism arrangements to the dangers of Climate Change. However, they can work as powerful tools to guide governments, investors, companies, and consumers to make more informed decisions. These projects could consequently lead to more transparent operations and accountability, as well as provide no excuses for agri-food actors to not prioritize the environment.

"Justice is not blind, it is only paid to be."

Nayani Teixeira @ Unsplash

"Justice is not blind, it is only paid to be."

Nayani Teixeira @ Unsplash

Yet, a possible solution that is not as obvious could be found on the streets. In 2019, for example, protesters worldwide held a global climate strike, showing their discontent with the interests of big companies in doing business at the cost of the planet's survival. This led to a surge in public displays through demonstrations and civil disobedience actions that helped ignite discussions about the challenges we face due to Climate Change.

What we can see is that by combining the cooperation of social movements and civil society, with the aim of preserving the planet we inhabit, and the use of technological tools we have at our service, we could create strong networks as a powerful engine for social change for both nations and local communities. By joining the Global South and the Global North as an unseparated alliance, modern society could challenge mainstream institutions more effectively. Considering that protests are growing considerably, communication and transparency are at the core of any potential change. With the rapid adoption of social media platforms aiding activist groups to sway public opinion, the course of mobilization and action against Climate Change may look quite different in the years to come.