Gender & Tech

Laura Del Vecchio

National Cancer Institute @ unsplash.com

The world has become increasingly more interconnected and reliant on technology in the past years, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. With ever more schools adopting distance learning methods, companies transitioning to remote work, and the expanding presence of Artificial Intelligence in virtually all sectors, digitization is becoming entrenched in all aspects of life. However, though this transformation is expected to produce very positive results, there are existing gaps in access and usage of digital technologies, commonly referred to as the “digital divide.”

The term “digital divide,” according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), means the “[...] gap between individuals, households, businesses, and geographic areas at different socio-economic levels with regard both to their opportunities to [technology] access and their use of the Internet.” In other words, characteristics such as gender, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, location, educational background, and political- and socio-economic status can be either an impediment or an advantage to access to and distribution of digital technologies but also a constraint hampering the competencies acquired through the application of these tools.

While the implementation of some technologies facilitated women’s empowerment in various sectors of their lives, these tools still reproduce patriarchal dynamics as well as exclusive structures designed by and for men. In terms of access to mobile internet, there are still over 230 million women without internet connectivity. And, women are 7% less likely than men to possess their own mobile phones.

If we stress these figures to women with lower levels of digital literacy, deprecated incomes, or living in rural areas, access to digital tools is even more detrimental to their emancipation in the digital transformation. Summing up with the fact that women and girls have been historically disadvantaged from enrolling in many sectors, such as the economy, education, labor market, etc., this could systematically prevent the inclusion of this societal group from participating actively in the digital transformation.

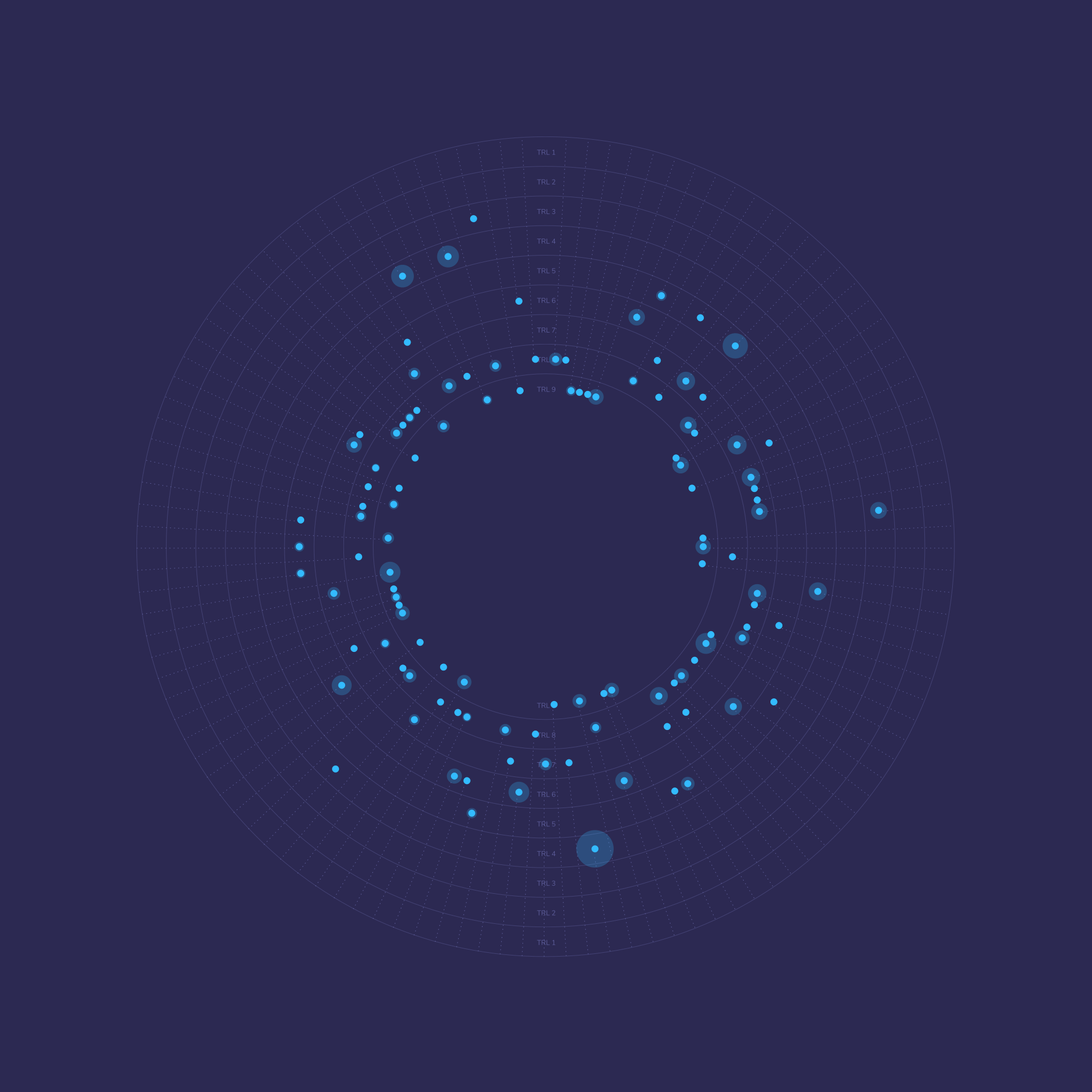

The amplification of online and technological developments has increased gender inequalities worldwide. This is a reality, and a disturbing one. As an effort to reflect on the impact of emerging technologies and how they may directly or indirectly affect gender relations and their structures of power, the Sector and Global Projects Division (GloBe) from GIZ's operational divisions, together with Envisioning, organized a roundtable intended to break down the major digitization trends and the associated impacts on marginalized groups such as women, girls, and LGBTIQ+ community, aiming at identifying potentials that derive into and formulate concrete recommendations for action.

The present article contemplates the discussions held during the roundtable. It is structured as an interview as the interventions were orientated towards specific challenges facilitated by Thiara Cavadas, partner and head of research at Envisioning, and the panelists. The panelists are experts in developing strategies, plans, and technological solutions that can support an equal digital ecosystem and were summoned to disclose their current methodologies and elaborate collective tactics towards a more inclusive world for women, girls, and LGBTIQ+ identities.

Roundtable participants

Thomaz Rezende @ Envisioning

Roundtable participants

Thomaz Rezende @ Envisioning

The article is divided into two sections, which were the main technology trends identified to play a major role in the future of development cooperation: Data & AI and Platform Economies. Each section is segmented by the corresponding questions raised throughout the roundtable, in which the speakers shared their experiences, projects, and additional insights. Ultimately, these sections employed some technological applications to bring real-life examples to the sections affecting the inclusion of women in the digital transformation.

You are now invited to discover the insights shared during the roundtable.

Data & AI

Museums Victoria

Museums Victoria @ unsplash.com

Museums Victoria

Museums Victoria @ unsplash.com

The compound annual growth rate of the AI market is expected to increase by 40.2 % in the upcoming years. The market is already at full speed embracing (and investing) in AI/Data trends, so ignoring them is not an option. The risks our panelists raised about these technologies are present but not immutable, and minimizing their impact on women and other minority social groups must become a top concern for development cooperation.

How Can Data & AI be Used to Foster Gender Equality?

Vanessa Hochwald brought two examples illustrating the potential impact some AI technologies could produce on women: Social Program Matching Database and Facial Recognition.

In terms of gender equality, Facial Recognition could implement forms of monitoring to ensure safety and autonomy in the public sphere, possibly helping in family reunification at critical times (e.g., identifying shared physical traits and connecting relatives automatically). According to Hochwald, “[...] it could also improve access to goods and services for women without the possession of legal documents, independent of spouses or other people.” For illiterate women, for instance, this technology could serve as a toolbox enabling more efficient transactions in the financial system, thus facilitating this societal group into entering economic markets, as well as labor.

Also, Facial Recognition tools could play a pivotal role providing a backup when documents are lost, stolen, or damaged, in which documentation would be safely stored in the cloud and retrieved easily whenever appropriate. Instead of handing their IDs to officials, for instance, individuals could scan their faces and automatically link their biometric traits with the data contained in legal databases.

For the Social Program Matching Database, marginalized groups, including women, could receive proper aid programs tailored to their needs. As the database would contain their personal information, illiterate women would have increased access to social programs more efficiently, even decreasing the risk of filling out information incorrectly or missing deadlines for applying to an aid fund.

In general, these tools could, in Hochwald’s words, “help all citizens benefit from a more lean, tamper-proof and error-proof administration of social services, and Data, together with AI, could unlock hidden patterns of additional positive outcomes.” These technologies could function as integrative catalysts towards achieving an equal digital ecosystem, thus helping deliver the right benefits to the right people at the right time.

The New York Public Library

The New York Public Library @ unsplash.com

The New York Public Library

The New York Public Library @ unsplash.com

What are the Unintended Consequences of These Examples to Gender Equality?

Salomé Eggler stresses that, in terms of cybersecurity, “[...] a centralized database [such as the Social Program Matching Database] is a potential risk since it can be hacked, and sensitive personal data of women might get into the wrong hands.” The shortcomings of databases include potential concerns about data and privacy if there are no layers of data protection or regulations that ensure data ownership and security.

Related to the Facial Recognition tool, in the Kenyan context, Eggler mentions the national biometric identity program, which has been compiling facial photographs from citizens. This system, according to Eggler, “[...] has been temporarily suspended by the High Court because of data protection concerns and to safeguard minorities from discrimination.” She adds, “if agencies and organizations have access to the information on the database, it can be a door opener for tracking and profiling” users according to their individual characteristics, such as gender and race.

Can you imagine a future where national biometric databases are mandatory? This could elicit a considerable decrease in criminality rates and related incidents. Still, the data contained in these datasets could discriminate against minority groups or be used for illegal reasons. Indeed, according to Eggler, “the private sector actors with access to biometric databases built on Facial Recognition tools could make incorrect use of the technology, such as to spy on ex-spouses or girlfriends,” a practice commonly referenced as “function creep”, when information in digital environments is used for purposes that do not correspond to their original aim.

There is a thin and complex line between providing security and enabling control mechanisms. Eggler explains, “[...] if even a single attack is prevented, the technology is worth having. Such reasoning is often ill-founded. Surveillance technology does not necessarily keep us safe. In many instances, surveillance technologies also decrease our security.” Accordingly, Facial Recognition data is typically gathered without the consent of the data subject. While biometric databases promise to keep our lives safer, which subsequently lead users to agree to cede data in exchange for their security, by aggregating information without users’ consent, these systems could violate users’ right to privacy.

Beyond the General Threats of Digital Solutions, Are There Other Negative Consequences Directly Related to Data Collection and Artificial Intelligence Analyses?

Machines understand gender in two limited ways: explicitly and implicitly. According to research, “implicit” machine perception occurs quickly, normally with limited information. Differently, “explicit” machine perception requires the comparison between obtained features (when a machine detects someone’s face) and related knowledge (data added to the algorithm). Facial Recognition is an “explicit” example. Typically, it separates people into male and female, which directly puts non-binary people out of the equation. These systems are generally trained to process gender through visual expressions, such as short hair = men and long hair = woman.

People who do not fit into these standard categories are systematically misrepresented by the algorithms inserted in Facial Recognition tools. According to Beatrys Rodrigues, “[...] in order to see gender, systems developers are the ones stating where gender is: gender is in the facial hair, or how long or how short it is. But we know that gender is not binary and that people have a multitude of physical traits. Especially because most machines are trained in datasets that do not have an international perspective, and exclude people with diverse characteristics different from male-caucasian traits.”

She adds that “[...] machines could also flag gender bias implicitly. I think the most notable example is when Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak says Apple Card offered his wife a lower credit limit. Even though supposedly, the algorithm was not built to differentiate by gender. Another example is from the Trans Communications scholar Sasha Costanza-Chock, who has shared how they¹ are always subject to patting in airports, often causing uncomfortable situations when the airport machine flags their body as something menacing, merely because of its binary preprogrammed division.”

Eggler appends that, concerning Facial Recognition and Social Program Matching Database, “[...] algorithmic biases and social sorting can affect the LGBTQI community and, especially women of color who are more prone to be incorrectly matched than men.”

¹ In order not to fall within the gender binary he/him/his or she/her/hers, we decided to use “they,” a gender neutral pronoun that intends to foster an inclusive communication system, to reference the Trans Communications scholar Sasha Costanza Chock.

What Are the Options to Circumvent These Issues? What Can Organizations in Development Cooperation Do to Become More Gender-sensitive?

It is imperative to guarantee that women’s demands are appropriately represented in the development of technological solutions. The lack of women enrolling in decision-making and the development of digital technologies results in services and tools designed only by and for men, without considering women’s real requirements. According to Helene von Schwichow, “[...] we need to have a closer look at the development of AI technologies. A cause of algorithmic bias and thus discrimination is clearly the absence of representation in the datasets. This is partly due to the fact that AI technologies are being developed by a homogenous group of people (white, male, healthy). In order to have more diversity in the data sets, we need more diverse teams.”

Angela Davis

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

Angela Davis

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

She continues, “to achieve more diversity and interdisciplinarity in AI development teams, the access to the field needs to be facilitated for women and queer people.” Combining these efforts could be escalated gradually: if companies hire more diverse teams, more different perspectives would be represented in the datasets, biases could be decreased in number, and consequently, datasets would become less discriminatory.

The digitalization process has emerged with various hurdles for women, the trans community, and non-binary people, including the ever more patent marginalization of their voices in the development of digital tools. While digital literacy offers new ways to tackle rooted gender inequalities, there is no doubt that sound policies are needed to warrant that all individuals, despite their differences, can reap the advantages of digitalization. Eggler emphasizes that if these tools are designed together with the user, "Digital Principles for Development would be brought to life."

Related to privacy and data ownership, Eggler says that there is a latent need in “[...] ensuring that data collection and storage are not centralized, so that in case of any possible attack, not all data is subsequently exposed. Governments, international organizations, and the private sector would have to create models for secure communications in databases, including providing end-to-end encrypted traffic as far as possible, as well as institute ‘privacy by design’ principles in the system. They would also need to provide additional transparency in terms of disclosure of cybersecurity policies, and regulatory bodies would have to provide a legal and policy framework that incentivizes reporting and disclosure of vulnerabilities, sometimes even taking steps to notify affected parties in case of a breach of data.”

From a legal perspective, regulatory bodies need to provide by law “[...] a defined and restricted scope of use for the technology, make enrollment and use as voluntary as possible, as well as create independent and well-designed mechanisms for grievance and redress.” From a design perspective, Eggler adds, “[...] the use given to the data should be limited to the purpose by which these data are collected and used. Governments and international organizations need to put in place proper measures to prevent user profiling based on the data volunteered, grant individuals' rights related to their data, such as accuracy, rectification, and opt-out, institute robust data protection frameworks, help minimize the amount of and type of data governments and associated service providers collect, and restrict lawful interception (access) of the database and implement measures for accountability.”

Eggler concludes, in order to build a long-term infrastructure that can conform gender equality, “we need to move beyond interpreting gender-sensitivity in digital projects as using tech for ‘women issues,’ but making all issues include gender.”

Platform Economy

Women marching

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

Women marching

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

From its outset, the Platform Economy was perceived as a more inclusive and open model compared to traditional economic models. Although most of these platforms, such as Airbnb, Deliveroo, Glovo, BlaBlacar, etc., send the message of providing equal opportunities to all its users, many studies suggest that Platform Economies exacerbate segregation and the gender gap, also present in traditional economic models.

This is partly because the largest number of these platforms are based on profit-making approaches (exemplified by what is commonly referenced as "unicorn companies"), and those with a prosocial focus mostly related to cooperativism and equality standards have less visibility in the digital realm. However, within platforms operating through prosocial frameworks, the participation of women is even lower than in unicorn-types. A clear example is that of Wikipedia, with an average of 12% of female editors. Furthermore, a study from the European Commission shows that women embody 30% of programmers in the private sector while they only represent 1.5% in the open-source industry.

So the question is:

How Can the Platform Economy Foster Gender Equality?

To answer this question, Hochwald exemplifies with the technology application Bartering Platform and gives a wealth of examples of how this technology could bridge the gender gap. According to her, “[...] digital platforms can help women build capital, improving the ease of exchange compared to traditional methods, thus possibly increasing the value of typically female-based activities, such as unpaid domestic and household work.”

She adds, “because the platform is not based on the ownership of physical money, it could offer more economic opportunities for women. This type of Platform Economy promises openness, equality, and flexibility, and it is desirable for people who have additional obligations such as care work, which are still mainly women.”

What Are the Unintended Consequences of this Example? What is the Lived Experience for Women in the Platform Economy?

According to Von Schwichow, “Platform Economies promise openness, flexibility, and transparency. Yet, studies show that they do not eliminate but pursue and amplify gender stereotypes and social inequalities.” According to her, “women are still more likely to work for a meager income and to be affected by old-age poverty, as well as to experience sexual harassment in their work environment,” in which, conversely, “they have minimal options to report such acts of violence in the Platform Economy.”

Together with MOTIF Institute for Digital Culture Von Schwichow conducted qualitative research to evaluate the lived experiences of women who work on Platform Economies, such as Airbnb, Helpling, or 99designs. Their study showed that, although the platforms offer “[...] flexible work in terms of time, place, number of hours worked, low entry barriers, and little bureaucracy, they reproduce insecure work standards, including legal insecurity, financial insecurity, lack of social security and retirement provision. They do not offer any protection to the employees,” thus evidencing precarious labor conditions to more marginalized groups of society, such as women. Also, she adds, “[...] women are more likely to experience sexual harassment and are expected to do more unpaid extra work such as care work.” As women have historically been subscribed to the role of caretakers, these platforms reproduce stereotypes where women have to be “[...] more careful with the maintenance of their own profile, always being nice and supportive, listening to the clients' problems, etc.”

Rodrigues continues, “we know that these platforms have been an economical alternative for many women around the world, and have been helping a lot of people secure an income, especially during the stay at home mandates of the pandemic, but workers on platforms such as Onlyfans and Patreon have been experiencing what is known as ‘aspirational labor,’ where workers spend uncountable hours in thinking about the possibility of future rewards, such as answering messages, following/unfollowing users, analyzing other content creators, etc.” This, according to Rodrigues, “[...] continues to enact historical labor conditions where women’s work is invisibilized while the platforms are still profiting from their unpaid work.”

In addition, part of the problem that persists in the digital environment when we talk about women and employment is the lack of transparency. Von Schwichow adds that “the non-transparent work within this economic model,” represented by remote work and distance among workmates, “incites further obscurity on how the payment for the work done is performed” as well as puts increased barriers to contact the platforms themselves, as the “[...] isolated work produced by the absence of networks between peers generates a one-sided relationship to the platform,” leading workers to feel less empowered and likely to experience feelings of solitude and abandonment.

On a more nebulous note, according to UNESCO, 73% of women have, at some point in their lives, been exposed to some sort of cyber-violence. In the case of women lacking access to digital literacy, they have fewer resources to cope with possible cyber attacks. Eggler exemplifies the Kenyan experience with cyber violence, saying that “[...] 1/4 of all women in Kenya have already experienced cyber harassment. Women participants, especially in the creative sectors, face the expectation to sell their products cheaper than men or face harassment or a vote down via ratings on platforms more quickly than men.”

Women in tech

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

Women in tech

Library of Congress @ unsplash.com

What are the Options to Circumvent these Issues? What Can Development Cooperation Do to Make the Platform Economy more Gender-sensitive?

Von Schwichow stands firm that we should “challenge the role of algorithmic management, and ensure flexibility of work by abolishing punishment mechanisms.” In her opinion, state actors could “[...] create opportunities for cooperatives and interest groups, ensure the minimum wage for platform workers and recognize invisible work (such as maintaining the profile, customer communication, and organization of work), state regulatory solutions to protect these workers from precarious living and labor conditions, provide a clear legal and tax framework for platform work, offer more support programs, and further training opportunities for women in tech.”

On the other hand, Platform Economy organizations could, according to Von Schwichow, “[...] guarantee regular, clear communication and punctual payouts. If possible, Platform Economies could altogether process payments by working hours,” thus providing fair salaries in accordance with the amount of work performed. She continues, “they could also use the statutory rate, minimum wage, and laws to protect workers, such as the right to take breaks into account. They could also inform workers about legal and tax regulations and have ready-available support.”

Von Schwichow appends that organizations should “protect against and take responsibility in case of (sexual) violence and discrimination.” For this to happen, she concludes, companies would need to “ensure communication between the platform and the workers.”

What Are the Possibilities of the Platform Economy for Development Cooperation? What Does GIZ Have to Consider for Future Projects and What Can be Done Now?

According to Eggler, “offline and community-based interventions are necessary to empower women to use digital tools.” In order to increase women’s access to digital platforms, non-mixed environments are necessary, such as those reserved only to women, the trans community, and non-binary people. Eggler exemplified that ”the Project Rubicon of the Kenyan organization Mawingu showed that in-person women-only events were the most effective to onboard women to the digital world.” They also reported that “women and girls used digital platforms more often when they were ‘invited’ by someone to join the platform,” thus generating additional strategies to make digital environments more welcoming and friendly to those that have been excluded from participating actively.

Eggler underlines that to keep women participating on digital platforms and provide the necessary instruments to fight online harassment, “[...] GIZ could build the capacities of women and girls but also platform providers in addressing and fighting gender-based online violence.” She continues, “another GIZ project seeking to make women’s experience online safer is Bytes of Freedom. The project develops online features and functions for Social Media interfaces allowing women to easily moderate, report, and find support when faced with gender-based online violence.”

Additionally, raising awareness and training on digital rights is a critical tool to prevent cyber crimes against minority groups. It is key to critically analyze the underlying causes of gender inequality gaps in digital environments, such as providing capacity building to women and girls about the rights they hold and what they can do to act against violations of their rights. Eggler provides an example that could strengthen this, which is, in her words, “The Digital Transformation Center Kenya, a project supporting capacity development for women and girls when it comes to knowing and enforcing their right to privacy.” On the same note, she adds that “the Gig Economy Flagship is an additional project through which GIZ seeks to strengthen the rights of gig workers through training but also the development of rights-respecting regulation for the platform economy as well as digital indexing platforms against unfair work principles.”

Britta Scholtys calls attention to efforts that “[...] could build allyship between platform providers and women, strengthen women's capacities to address gender-based online violence, as well as additional actions to advise on the development of rights-respecting policies for work in the Gig economy.” According to her, all these strategies could constitute assets that provide a wealth of opportunities to access, self-expression, and empowerment to marginalized groups of society.

Final Remarks

Women operating in telecom

Museums Victoria @ unsplash.com

Women operating in telecom

Museums Victoria @ unsplash.com

Hochwald reminds us of an important issue, “there is no way of reaching the SDGs, especially SDG 5 (Gender equality), without the use of digital technologies. These technologies are being adopted everywhere, whether we want them or not. We, therefore, have to know about them and how we can harness their potential for our work, thus minimizing possible unintended risks.”

Indeed, without assessing the impact of emerging technologies and technological trends, development cooperation could lead to ineffective and superficial measures that do not interplay with the demands and needs of specific societal groups, such as women, the trans community, LGBTQI+ individuals, and non-binary people. Approaching the hidden motives of digital gender gaps is indispensable when facing the symptoms that cause inequalities in the digital realm.

The actors involved in implementing digital technologies should keep an eye on distinguishing the primary sectors where gender gaps are encountered. They should also pay increased attention to the intricate synergies between technological barriers, dominant views of society, and political-, cultural- and socio-economic factors to encompass gendered characteristics as a valuable item to interact with social circumstances reproduced in digital environments.

According to Rodrigues, technology should not be seen as the agent of change itself, as there is no single "digital solution for everything, or a one size fits all. As per Design Justice principles, the impact on the community should be prioritized over the intentionality of the designer. Think of networks, the commons, over usability: how can we facilitate fair community exchanges and human development? We should get inspired by projects that promote solidarity, and then think about scale.”

For Von Schwichow, technologies do not just exist in a void. “They are developed by humans who have certain backgrounds, certain values, and certain perspectives. Their mindset is transferred into the technologies and can lead to discrimination. But nothing needs to stay the way it is; technology can be discussed, challenged, and changed. A first step would be to advocate for more diversity in developer teams because research shows that more diverse teams develop more socially just technologies.” On the exact reflection, Scholtys points out that “we have to strengthen digital skills and literacy, including data protection,” which leads to what Eggler mentioned about the design principles of digital technologies, where every digital initiative should be based on cultural and legal aspects to capture the cross-cultural variations for gender-specific needs and constraints. This could help force planning and development strategies to be approached and debated from different perspectives.

All in all, the strategies shared by the panelists intend to provide efforts to an ongoing mission we will face in the upcoming years. In order to strengthen investment on a healthy gender perspective capable of empowering and reducing inequality between gender identities, all solutions should provide tailored opportunities to every community, such as designing value systems aligned with life perseverance objectives set by individuals and communities. On one hand, there must be an intersection between equality and social cohesion in global relationships to include women at all participatory levels of society. On the other hand, non-sexist and non-discriminatory technological solutions should bridge equal access among all individuals, thus empowering people in situations of discrimination and disempowerment.