From Hype to Hyperlinked: The Supply Chain of Tomorrow

Alex Turner

Jan Folwarczny @ Unsplash

Abstract

This future scenario considers how emerging technology could disrupt the supply chain over the next decade to provide traceability and transparency, particularly for the benefit of small independent suppliers living in environmentally fragile regions. We recognize the challenges and drivers that are forcing supply chains to evolve. Global trade is now an ecosystem valued at more than $22 trillion, yet the complex structures of global supply chains and economies hide the true costs of the negative externalities. Regional trade agreements and subsidies are benefitting developed economies at the expense of the ecosystems and biodiversity of developing countries. Today, supply chains enslave more people than at any other point in human history. Business, if not governments, must do better, which is why we look to the supply chain of the future: a ubiquitous, automated, and predominantly circular supply chain. Four key requirements are driving change towards the Hyperlinked Supply Chain: traceability, transparency, accessibility, and circularity. We identify emerging technologies that may be key in responding to these drivers. In particular, we look to technologies that provide traceability and transparency in supply chains, such as Blockchain solutions, barcode tracing software platforms, nanotagging, and bartering platforms that can be used to create a more streamlined supply chain and facilitate access to new markets and finance, which go some way to address economic inequalities. In examining the potential of these technologies, we also look to the challenges and opportunities posed by their implementation, in particular how this could impact small-scale producers and consumers. Finally, we consider the economic, ecological, social, and political opportunities and challenges that the Hyperlinked Supply Chain could present.

Free trade was heralded as the key to a prosperous future for all, developed and emerging economies alike. Yet globalization poses a unique set of challenges. Can technology provide protection for those most at risk from the negative externalities of global trade? Can technology give the smaller independent producers better tools in the supply chain to overcome the inequalities stacked against them?

The Case for the Hyperlinked Supply Chain

In 2020, nearly half of the world’s largest companies failed to provide any evidence of identifying or mitigating human rights issues in their supply chains. Practices such as mass production, leader pricing, and same-day delivery have lulled consumers into a false sense of availability and affordability while the often ugly realities — or negative externalities — of the supply chain are hidden from sight (and market price). Rather than the consumer paying the cost, the costs of such negative externalities are often born by the most vulnerable and least protected: labor forces, producers, and the environment.

The advance and development of supply chains are often couched in terms of how they benefit businesses or consumers: maximizing profitability, optimizing logistics, improving volume flexibility, improving customer experience, and increasing customer retention. Rather, this future scenario explores the role of technology in providing mechanisms for transparency, traceability, and accountability in order to support more equitable and sustainable economic development.

We look to the hyperlinked supply chain: a symbiotic articulation of digital technologies and tools across a ubiquitous, automated, and predominantly circular supply chain. In particular, we lift the veil to explore how the hyperlinked supply chain could impact arguably the most important element: the producers.

Lack of Transparency: Contemporary Supply Chains Conceal Hidden Costs and Negative Externalities

In recent years, the acceleration of agricultural trade, especially in emerging economies like Brazil and Mexico, has exacerbated negative environmental effects such as environmental degradation, deforestation, groundwater exhaustion and transboundary pollution, and puts already endangered regions at risk of loss of species and ecosystem services. The environments of developing countries suffer while developed nations benefit: since 1993, for example, greater corn trade for supply to North America under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has come at the expense of deforestation and biodiversity loss in Mexico.

Photo by Marek Piwnicki on Unsplash.

Marek Piwnicki @ Unsplash

Photo by Marek Piwnicki on Unsplash.

Marek Piwnicki @ Unsplash

According to WTO annual data, global trade is an ecosystem valued at more than $22 trillion. Critically, this value is not distributed equitably or ethically across the globe. Global supply chains rely on cheap labor and often companies will base operations around such availability.

In 2020 the United Nations estimated that 152 million children, nearly 7% of all children worldwide, are in child labor, with 72 million engaged in hazardous work. For many of the ≈190 million women who work in global supply chains, the reality is not economic independence, but low wages, unsafe working conditions, and harassment. Almost 50 percent of farm labor is performed by women, but they hold only 15 percent of farm land. It is not easy to eradicate issues of unethical labor and carbon footprint when demand for cheap goods like fast food and fast fashion is so prevalent, and the global economic system is built on the concept of growth and GDP.

Child Labor Global Distribution Map

World Mapper @ Worldmapper.org

Child Labor Global Distribution Map

World Mapper @ Worldmapper.org

A digital gap both in terms of access to technology by developing countries and by businesses means that developing countries continue to lag behind. Almost 80 percent of the world’s poor and food insecure live in rural areas, mostly depending on agricultural production for their subsistence. Over 90 percent of farms globally are run by an individual or a family and rely primarily on family labor, and produce more than 80 percent of the world’s food in value terms.

Thus far technological advances have disproportionately advantaged the Global North through the accumulation of wealth and improvements in quality of life. This creates a loop: with wealth concentrated within the hands of so few, so is access to technological innovation.

The primary challenge that perpetuates inequality in supply chains is a lack of transparency. Traceability is not a legal requirement across all industries, and with myriad national and supranational systems and legislation that regulate different jurisdictions and sectors, cross-border trade can be complicated and opaque. The not-for-profit GS1 develops “global languages for business” designed to harmonize transnational regulatory requirements, but further collaboration and cooperation are needed to create robust, coherent, transparent, and truly sustainable systems.

Hyperconnected Omniscient Commerce

Consider a future scenario where Northern nations have assimilated above and beyond a regional trade agreement. It is 2030, and Global Human Rights Due Diligence Regulations, based on the success of Germany’s Law to Regulate Human Rights and Environmental Due Diligence in Global Value Chains, have recently come into effect, proving instrumental in improving livelihoods, reducing forced and child labor, and creating a fairer, more transparent, and greener supply chain. Consumers enjoy access to real-time updates on their shipments of fresh produce straight from the fields to their fridges, meanwhile, subsistence farmers in Ethiopia battle the digital gap, intense droughts, and generational legacies of debt bondage.

Hyperlinked Supply Chain

Maxim Hopman @ Unsplash

Hyperlinked Supply Chain

Maxim Hopman @ Unsplash

Hyperlinked supply chains, an all-seeing, cloud-based eye, rule the global supply chain roosts. Digital Twins, replicating both products and the supply chain in a cloud-based model, operate from a control tower, providing end-to-end transparency, the ability to predict demand and respond to risks in real-time. These advanced supply chains offer both businesses and consumers greater insight and understanding to their product provenance, journey and destination. By also providing visibility and access to external agencies, including governments, NGOs, regulators and authorities such as INTERPOL, the Global Human Rights Due Diligence Regulations finally have the mechanisms they need to enforce transboundary sustainability and ethical labor laws. But is it up to governments to monitor and mandate how corporations behave beyond their borders? And could the hyperlinked supply chain become yet another tool to exploit vulnerable suppliers and exhaust natural resources?

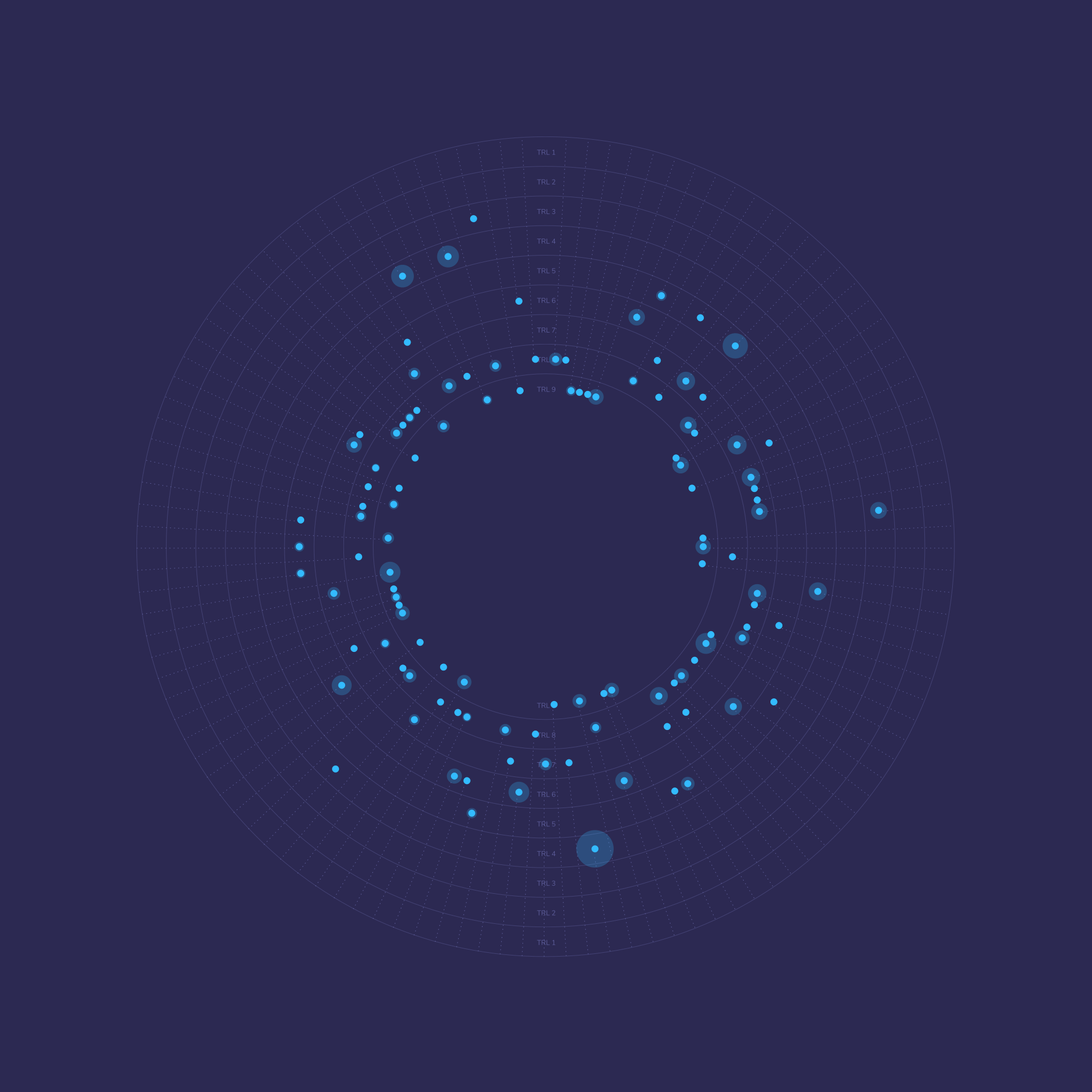

2030: The Drivers for the Hyperlinked Supply Chain

In this next section, we look at four key requirements for the supply chain of the future and how they are driving the development of hyperconnected systems and processes. Far from being a linear chain, hyperlinked supply chains are complex, diverse, and multidimensional ecosystems, operating over many conceptual layers and spanning vast digital and physical territories. Our aim here is to identify potential opportunities where emerging technologies could converge to create an entire ecosystem that can deliver value, as well as empower and protect vulnerable players.

Traceability: From Basic Barcodes to Satellite Solutions

End-to-end visibility over the supply chain is no longer a pipe dream. Contemporary supply chains have been beleaguered by complex, incompatible systems unable to communicate effectively with each other. By 2030, we can expect the complexity to be replaced by transparency: Digital Twins providing virtual replicas of entire supply chains, managed by smart control towers with unparalleled visibility into every nook and cranny of the supply chain. But how could this be achieved?

Supply Chain Oversight

NASA @ Unsplash

Supply Chain Oversight

NASA @ Unsplash

The not-for-profit organization GS1 develops and maintains global standards for business communication, the most commonly recognized being the barcode, a symbol printed on products that can be scanned electronically. The Unique Device Identification (UDI) is a globally standardized system that creates a globally unique label and a device identifier to ensure medical devices can be tracked and traced around the world, from distribution to end-use and decommissioning. As it expands into other industries and products in the supply chain, assigning an item or device with an internationally recognizable and machine-readable code will mean that information pertinent to the supply chain can be communicated quickly and easily.

The primary advantage of barcodes is that they are a low-cost solution and already in use in supply chains, thus minimal investment is needed on the part of the producer. Dutch confectioner Tony’s Chocolonely recently abandoned its endeavors with blockchain in favor of a simpler, more accessible solution to ensure that their supply chain is 100% free from slave labor. By pairing a simple and straightforward tracing technology such as barcodes with a cloud-based software platform, Chainpoint, the entire supply chain can be visible in real-time.

Cacao Pods

Alexandre Brondino @ Unsplash

Cacao Pods

Alexandre Brondino @ Unsplash

Emerging technologies in Nanotagging will also become more commonplace in supply chains. Active RFID Tags are high-tech solution capable of real-time location tracking by using transponders or battery-powered sensor tags to transfer data to the cloud and control tower. However, Active RFID tags are still an expensive option, and while such data can add auditable information relating to the supply chain to demonstrate ethical procurement or sustainability, the reality is that this adds to the burden of toxic electronic waste (e-waste). Illegal shipments of e-waste remain an issue: in 2018, the UK was identified as the biggest illegal exporter in Europe. Therefore, both reducing e-waste and being able to trace it is vital for sustainable, hyperlinked supply chains of the future.

As an alternative to tags, Invisible Traceable Markers have anti-counterfeiting pigment, encryption technology, and microscopic GPS, which can be digitally scanned and traced at any point throughout the supply chain to verify their authenticity. These markers provide more comprehensive and robust data than RFID tags to the user, although it requires encryption technology and devices such as mobile projectors or AR compatible readers. While this will go some way to address the e-waste issue, there remain challenges regarding inter-marker confusion, meaning that the markers may be misrecognized by the readers, introducing inaccuracies into the supply chain. Traceability also relies on actors within the supply chain having access to the readers, scanners, and encryption software, which are not always accessible to smaller, independent producers.

Externalities of Trade

Timothy Newman @ Unsplash

Externalities of Trade

Timothy Newman @ Unsplash

Tracing the means of transport involved in the supply chain is also pertinent so as to combat issues such as human trafficking — in Thailand for example, the International Labor Organization (ILO) found that up to one in six workers in the prawn-fishing industry had been forced into working against their will. Tracing is also necessary to combat “ghost ships” and other illegal practices in fishing which are extremely challenging to monitor. In the EU, up to €1.1 billion worth of illegal fish is imported every year, and these “ocean-grabbing” practices across the world are estimated to cost between $10bn and $23.5bn per year. Developing countries are thought to be most at risk from illegal fishing, with the total estimated catches in West Africa being 40% higher than reported catches. Automatic Identification Systems (AIS) is one technology that could address this. The Global Fishing Watch platform uses Satellite Automatic Identification Systems (Satellite-AIS), designed to prevent collisions and to detect and trace ghost ships to combat illegal fishing and human trafficking. The map displays Spatial Computing information, providing an almost real-time view of fishing activity around the world. When combined with IoT and even blockchain technology in the supply chain digital twin, real-time insights in shipping can be obtained. Policing the seas to reduce illegal fishing and protect vulnerable labor forces will then become much more feasible. (For more on this topic and how it relates to ethical labor, see our Labor Data article.)

Transparency — From Bitter Coffee to Digital Twins

Coffee is among the most popular beverages in the Global North, although it is grown almost exclusively in the Global South. Yet due to the structure of economics and the supply chain, the profits from coffee tend to stay in the Global North. Woefully the roots of the coffee trade are deeply entrenched in colonialism, and slavery remains an ongoing issue.

Wholesale Coffee Cost Breakdown

Allegra Strategies @ Financial Times

Wholesale Coffee Cost Breakdown

Allegra Strategies @ Financial Times

Sustainability Labels go some way to provide more transparency and traceability, but can also provide a shield for legal but unethical labor practices such as cooperative debt bondages. It is not uncommon for coffee workers to be indentured through forced labor or debt bondage, which can transfer to, and span, generations.

Smart Contracts enable complete traceability from the producer to the distributor, with every step in the chain of custody recorded in the ledger. Blockchain Certificates provide a mechanism for recording, demonstrating, and potentially rewarding verifications for ecological, social, and ethical practices in production — which are likely to become a crucial requirement for suppliers from developing economies seeking to trade in global markets. Using a Control Tower to monitor Smart Contracts and Blockchain Certificates could enable supply chain controllers to supervise more transparent transactions as well as address existing inequalities in global markets. For instance, if a product is discovered to be faulty, the distributed ledger can quickly trace, identify, and even solve the issue throughout the supply chain. This can be crucial for perishable or sensitive products such as fresh produce, food, and drugs.

Smart Contracts

Yasmim Seadi @ Envisioning

Smart Contracts

Yasmim Seadi @ Envisioning

By creating a Digital Twin of the coffee supply chain, for example, transparency in production and logistics can be monitored and verified. This has multiple benefits: consumers can trust in the provenance of their products and sustainability of the supply chain, and coffee growers can be fairly paid for their produce, and even incentivized to adopt sustainable practices. By incorporating Blockchain Certificates into transactions based on Crowd Farming platforms, for example, the Trado model, social impact, and sustainability data registered on the blockchain could be used to trigger early payment mechanisms to create savings that can be reinvested by the cooperative or the farmers themselves.

But hurdles still need to be overcome in both access and improving data security. The success of Blockchain Certificates for verification relies on every actor within the supply chain being able to access the platform or the blockchain to input or verify data in the first place. With NGOs needing to verify that sustainability requirements have been met, another level of complexity and the potential weak link is added to the supply chain, leaving it vulnerable to interference, corruption, and corporate greenwashing, where brands seek to maintain an eco-conscious identity for consumers and stakeholders while concealing on the ground operations.

'Money Landscape'

Niko Smirnov @ Behance

'Money Landscape'

Niko Smirnov @ Behance

The Oracle Problem is also a notable limitation of DLTs: that due to the intrinsic and central feature of immutability, blockchains are essentially deterministic, one way transactions, unable to pull in data from or push data to any external verification system (an Oracle). With the advance of Edge Computing and IoT-based solutions, this may be solved. But there remain further trust conflicts. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requires companies to delete client data once it has served its purpose. GDPR provisions on the “right to be forgotten” also lie at odds with blockchain, which, by design, stores data forever immutably on a decentralized ledger — unable to be deleted. Protocols and solutions thus need to be sought to reconcile GDPR with immutable data on global supply chain blockchains.

Accessibility: Bartering Platforms and Beyond

Over the next five years, International Data Corporation (IDC) predicts that every connected person in the world will have at least one digital data interaction every 18 seconds — likely from one of the billions of IoT devices, which are expected to generate over 90 ZB of data in 2025. But for this to be accessible to smaller, independent producers, the key lies in affordable conneted devices that farmers can use to perform a range of functions, from crop analytics and crop predictions, to bartering and trade negotiations — a core element in the supply chain.

'CropSaver' by Sergey Snurnik and Sergi Snurnyk on Behance.

Sergey Snurnik and Sergi Snurnyk @ Behance

'CropSaver' by Sergey Snurnik and Sergi Snurnyk on Behance.

Sergey Snurnik and Sergi Snurnyk @ Behance

The rise of low-cost Crowd Farming and Bartering Platform apps such as Wefarm allow independent farmers to share knowledge, access equipment and resources, and connect with both investors and buyers. Digital bartering platforms allow physical assets and services to be recorded and exchanged directly, without the need for intermediaries and middlemen. This is significant considering that in the coffee industry, for example, intermediaries account for up to 90% of costs. Certifiers can verify that certain standards or requirements have been met and add this to the platform. Every player benefits from transparency and traceability, with producers benefitting from revenue and investment, and consumers benefitting from a decentralized, immutable system that can demonstrate assurances on ethical and sustainable production and distribution in real-time.

Bartering Platform

Yasmim Seadi @ Envisioning

Bartering Platform

Yasmim Seadi @ Envisioning

Free-to-use apps create digital communities of farmers and producers, providing a network of support and information. Some, like Wefarm, can be used by SMS or other Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD) protocols, and are therefore not reliant on internet access. By making crowd-sourced information available to members, producers can help each other manage challenges such as drought, disease, and pestilence. They can also use the data to optimize yields, get market and pricing insights, source equipment, seeds, and fertilizers. The Ghanian-based Okuafo AI app has already helped 30,000 farmers reduce crop losses and improve harvests by 50%. Crowd Farming apps are thus likely to become the go-to resource for information, insights, and expertise, connecting and supporting small-scale producers and helping them optimize their operations, as well as access finance to create a more robust and more equitable economy.

Looking further ahead, Crowd Farming platforms could be also used to input data into In Silico Farming models. Current examples model data from real crops to simulate crop yields in response to changes in environmental conditions. With inputs from Livestock Monitoring sensors to diagnose ailments and monitor both animal welfare and environmental conditions, this could also extend to livestocking. In Silico Farming could thus become the basis of a Digital Twin in supply chains both in terms of responding to demand sensing and to model agricultural scenarios and forecast yields under specific conditions to optimize production, reduce costs, and manage risks such as the climate crisis.

Photo by Dirk Heseman on Unsplash

Dirk Heseman @ Unsplash

Photo by Dirk Heseman on Unsplash

Dirk Heseman @ Unsplash

By creating mechanisms to remove the middlemen and connect the producer directly with the consumer, the supply chain becomes less obfuscated and the logistics become more efficient and transparent. This low-cost and accessible technology is of great benefit to smaller-scale producers with tremendous potential to improve the economic prospects of many subsistence farmers. Demand sensing and hyperlinking producers with consumers in a streamlined, smart supply chain could also play a part in managing consumption more sustainably.

Yet, in order to stand up to due diligence audits, to be tamper-proof and robust enough to combat fraud, these platforms will require additional mechanisms or technologies to ensure robustness. Blockchain Certificates may be one way to achieve this. The applications of blockchain for the supply chain focus on transparency, traceability, sustainability, and compliance, especially in areas such as supplier payments, product traceability, and contract bids and execution. Blockchain’s data protection methods help build trust in transactions and provide a new source of data by which supply chain professionals can improve efficiency and visibility.

Circularity: To the Hyperlinked and Circular Supply Chain

Advances in technology allow the supply chain to become less wasteful, more sustainable and even closed-loop through practices such as reshoring and Remanufacturing. This brings the Regenerative Economy within far greater reach. Hyperlinked supply chains have a significant role to play in delivering this, by providing intelligent oversight and insight, from demand sensing and Anticipatory Shipping, to supporting IoT-connected self-repairing or self-replacing products.

Regenerative Economy

Joe Green @ Unsplash

Regenerative Economy

Joe Green @ Unsplash

The hyperlinked supply chain may also play a key role in managing Earth’s resources more sustainably. With the support of Nanosatellites and location data to monitor livestock and aquaculture, for example, a hyperlinked supply chain control center could also oversee farming practices and transactions to help sustainably manage production, or the supply and catch of protected or regulated species. (See our case study Digital Twin for more on how this relates to the diamond industry). By also combining data from hyperlinked supply chains with information and models relating to land use such as Remote Sensing Data and Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI), global-to-local approaches may finally become feasible, with global visibility over the impacts and actions being taken locally in real-time.

Providing the link between local solutions, national and global goals, adoption at this scale could lead to improvements in land-use monitoring and management and natural resources conservation around the world. (See Global Land Use Optimization for more on this). Such decisions rely on large-scale global collaboration, and it remains to be seen whether this is feasible by 2030. For example, major shortcomings in the global response to Covid-19 failed to contain the virus. An interim report provided to the World Health Organization (WHO) criticized national responses, describing a series of failures and deadly missteps that have cost hundreds of thousands of lives, deepened inequalities, and added to geopolitical tensions. Even now, nations cannot agree to work collaboratively to overcome the pandemic, with developed nations blocking developing nations from access to patent-free vaccines.

Photo by JT S on Unsplash

JT S @ Unsplash

Photo by JT S on Unsplash

JT S @ Unsplash

Ultimately, however, when the tools are available to lift the veil on supply chains, the concept of a hyperlinked supply chain could be used to implement policy from the top-down, rather than relying on the market which may not always be incentivized to be sustainable, as the accelerating climate crisis demonstrates.

Thus we believe hyperlinked supply chains can contribute to the rebalancing of inequalities between high and low-income countries, and inequalities within the country themselves. This requires rethinking in relation to distribution, which hyperlinked supply chains and DLT can achieve through symbioses in reshoring, upskilling workforces, and fairer trading practices, with the potential to tilt global economies back in a fairer direction.

What Does This Mean For The Future: The Outlook for Hyperlinked Supply-Chains

As solutions emerge with potential to close the digital gap and hyperlink supply chains, we can thus picture the symbiotic articulation of digital technologies and tools that empowers small-scale, independent producers, and increases transparency and traceability to significantly reduce the negative externalities and transactional friction currently plaguing the global trade ecosystem.

Gardens by the Bay, Singapore

Carles Rabada @ Unsplash

Gardens by the Bay, Singapore

Carles Rabada @ Unsplash

A cloud-based or edge system, interconnected throughout the supply chain and managed centrally by a control tower, could handle the many logistical and transaction-based tasks. Supply and demand will be anticipated and managed with demand sensing based on data from both producers and consumers: by tracking consumption patterns through embedded sensors or blockchain nodes, connected appliances will use algorithms to monitor and calculate operational needs. End-to-end visibility will be achieved through a synergy of technologies and collaboration with law enforcement bodies to ensure that regulations and legal requirements are adhered to. Consumers will be able to choose their suppliers, pick their own produce, and each participant in the supply chain could view the progress of goods through the supply chain, quickly discovering the location of products in transit by Delivery Robots and Delivery Drones.

Further ahead, this hyperlinked supply chain might even replace supermarkets and fulfilment centers, with delivery drones and robots making deliveries of sustainably sourced produce directly to our refrigerators. What if consumers are not inclined to make sustainable choices? Perhaps the refrigerator’s AI-powered decision-making on replenishing supplies is driven by a morality engine that makes ethical consumption choices for us, if we are willing to give our tools the power to make decisions on our behalf. This is where the future of hyperlinked supply chains meets Acommerce — autonomous commerce.

We foresee the ability of hyperlinked supply chains to incentivize an inclusive, resilient and circular economy, building in representation, participation, and empowerment of smaller-scale producers. Hyperlinked supply chains and their omniscient control towers could even play a role in ensuring that humanity does not renege on its duty to be a good steward of the Earth.

This can only be done by redressing imbalances in the current supply chain, to tip the scales away from customer satisfaction and profitability and towards empowerment of producers, giving weight to and visibility over mechanisms to achieve social and environmental objectives, and ultimately responsible stewardship of the planet, which, of course, can be verified in transparent, end-to-end traceability.

Opportunities & Challenges

Economic Opportunity

Advancement of circular economies through the practice of reshoring

Reshoring means bringing manufacturing and services closer to home to capitalise on automation and robotics to achieve shorter delivery times and reduced costs. With goods and services being consumed and recycled closer to their site of manufacture, the circular economy becomes more attainable. Hyperlinked supply chains also provide income generation opportunities in rural areas which can support local, circular economies.

Economic Challenge

The Leaky Bucket Case

In deploying AI applications to reverse outsourcing and bring manufacturing closer to home, commentators warn of increasing the poverty gap within and between countries. While this can be countered through initiatives such as community wealth building, closed-loop economies are easier to create and maintain at a smaller scale with the right political buy-in, but harder to manage at a macro scale.

Ecological Opportunities

Cleaner ports and distribution channels

As we move from physical products to digital products, and with the deployment of edge computing and the increase in autonomous vehicles and ships, combined with potentially shorter shipping routes as a result of reshoring, ports can become smarter, cleaner, and smaller.

Preservation of biodiversity

Strengthening the position of smaller producers in supply chains is vital for preserving and safeguarding biodiversity, culture and natural heritage. Practices and trends within the Hyperlinked Supply Chain such as reshoring also drive ecological benefits such as reduced deforestation.

Social Opportunities

Reducing inequalities in poverty and reducing human deprivation

Supporting and empowering small-scale producers and subsistence farmers allows them to better serve their communities, and create income generation opportunities in rural areas to improve rural livelihoods. Crowd farming promotes knowledge- and experience-sharing, particularly among women who perform 50% of farm labor, and can thus help to achieve political, social, cultural, and economic progress towards gender equality.

Traceability increases safety and reduce counterfeiting

Real-time, comprehensive and immutable tracing of products from the point of manufacture to the point of use via hyperlinked supply-chains, IoT, DLT, and edge computing is essential to preventing counterfeit pharmaceutical products and devices from entering the market.

Social & Technological Challenge

Internet availability for the Internet of Things in the supply-chain

IoT devices are reliant on internet connectivity to transmit data to the cloud. Edge computing is a solution for this, but still, 40% of the global population remain unconnected to the internet in 2020. For these technologies to be deployed, this inequity must also be addressed.

Political Opportunity

Global collaboration between government, law enforcement agencies, regulators and NGOs via portals in the Hyperlinked Supply Chain can improve conditions within global supply chains, reduce corruption and support policies to better manage global resources.

Political Challenge

International cooperation is required for transnational trade to create coherent, transparent systems

Traceability is not a legal requirement across all industries, and with myriad national and supranational systems and legislation that regulate different jurisdictions and sectors, cross-border trade can be complicated and opaque. G1 is an international organization that goes some way to harmonize transnational regulatory requirements, but further collaboration and cooperation are needed to create robust, coherent, and transparent systems.